Dear friends,

Welcome to May and welcome to the Observer’s first monthly commentary. Each month I’ll try to highlight some interesting (often maddening, generally overlooked) developments in the world of funds and financial journalism. I’ll also profile for you to some intriguing and/or outstanding funds that you might otherwise not hear about.

Successor to “The Worst Best Fund Ever”

They’re at it again. They’ve found another golden manager. This time Tom Soveiro of Fidelity Leveraged Company Stock and its Advisor Class sibling. Top mutual fund for the past decade so:

Guru Investor, “#1 Fund Manager Profits from Debt”

Investment News, “The ‘Secret’ of the Top Performing Fund Manager”

Street Authority, “2 Stock Picks from the Best Mutual Fund on the Planet”

Motley Fool, “The Decade’s Best Stock Picker”

Mutual Fund Observer, “Dear God. Not again.”

The first sign that something might be terribly amiss is the line: “Thomas Soviero has replaced Ken Heebner at the top” (A New Winner on the Mutual Fund Charts, Bloomberg BusinessWeek, 21 April 2011). Ken Heebner manages the CGM Focus (CGMFX) fund, which I pilloried last year as “the worst best fund ever.” In celebration of Heebner’s 18.8% annual returns over the decade, it was not surprising that Forbes made CGMFX “the Best Mutual Fund of the Decade.” The Boston Globe declared Kenneth “The Mad Bomber” Heebner “The Decade’s Best” for a record that “still stands atop all competitors.” And SmartMoney anointed him “the real Hero of the Zeroes.”

All of which I ridiculed on the simple grounds that Heebner’s funds were so wildly volatile that no mere moral would ever stay invested in the dang things. The simplest measure of that is Morningstar’s “investor returns” calculation. At base, Morningstar weights a fund’s returns by its assets: a great year in which only a handful of people were invested weighs less than a subsequent rotten year when billions have flooded the fund. In Heebner’s case, the numbers were damning: the average investor in CGMFX lost 11% a year in the same period that the fund made 19% a year. Why? Folks rushed in after the money had already been made, were there for the subsequent inferno, and fled before his trademark rebounds.

Lesson for us all: we’re not as brave or as smart as we think. If you’re going to make a “mad investment” with someone like “The Mad Bomber,” keep it to a small sliver of your portfolio – planners talk about 5% of so – and plan on holding through the inevitable disaster.

Perhaps, then, you should approach Heebner’s successor with considerable caution.

The new top at the top is Fidelity Advisor Leveraged Company Stock (FLSAX). Fidelity has developed a great niche investing in high-yield or “junk” bonds. They’ve leveraged an unusually large analyst staff to support:

- Fidelity Capital and Income (FAGIX), a five-star high yield bond fund that can invest up to 20% in stocks

- Fidelity Floating Rate High Income (FFRHX), which buys floating rate bank loans

- Fidelity High Income (SPHIX), a four-star junk bond fund

- Fidelity Focused High Income (FHIFX), a junk bond fund that can also own convertibles and equities

- Fidelity Global High Income (no ticker), likely launch in June 2011

- Fidelity Strategic Income (FSICX), which has a “barbell shaped” portfolio, which one end being high quality government debt and the other being junk. Nothing in-between.

And the Fidelity Leveraged Company Stock (FLVCX), which invests in the stock of those companies which resort to issuing junk bonds or which are, otherwise, highly-leveraged (a.k.a., deeply in debt). As with most of the Fidelity funds, there’s also an “advisor” version with five different share classes.

Simple, yes? Great fund, stable management, interesting niche, buy it!

Simple no.

Most of the worshipful articles fail to mention two things:

1. the fund thrives when interest rates are falling and credit is easy. Remember, you’re investing in companies whose credit sucks. That’s why they were forced to issue junk bonds in the first place. If the market force junk bonds constricts, these guys have nowhere to turn (except, perhaps, to guys with names like “Two Fingers”). The potential for the fund to suffer was demonstrated during the credit freeze in 2008 when the fund lost between 53.8% (Advisor “A” shares) and 54.5% (no-load) of value. Both returns place it in the bottom 2 or 3% of its peer group.

The fund’s performance during the market crash (October 07 – March 09) explains why it has a one-star rating from Morningstar for the past three years. Across all time periods, it has “high” risk, married recently to “low” returns. Which helps explain why . . .

2. the fund is not shareholder-friendly.People like the idea of high-risk, high-return funds a lot more than they like the reality of them. Almost all behavioral finance research finds the same dang thing about us: we are drawn to shiny, high-return funds just about as powerfully as a mosquito is drawn to a bug-zapper.

And we end up doing just about as well as the mosquito does. Morningstar captures some sense of our impulses in their “investor return” calculations. Rather than treating a fund’s first year return of 500% – when it had only three investors, say – equal to its fifth year loss of 50% – which it has 20,000 investors – Morningstar weights returns by the size of the fund in the period when those returns were earned.

In general, a big gap between the two numbers suggests either (1) investors rushed in after the big gains were already made or (2) investors continue to rush in and out in a sort of bipolar frenzy of greed and fear.

Things don’t look great on that front:

Fidelity Leveraged Company returned 14.5% over the past decade. Its shareholders made 3.6%.

Fidelity Advisor Leveraged Company, “A” shares, returned 14.9% over the past decade. Its shareholders, on average, lost money: down 0.1% for the same period.

Two other observations here: the wrong version won. For reasons unexplained, the lower-cost no-load version of the fund trailed the Advisor “A” shares over the past decade, 14.5% to 14.9%. And that little difference made a difference. $10,000 invested in the no-load shares grew to $38,700 after 10 years while Advisor shares grew to $40,100. little differences add up, but I don’t know how. Finally, the advisors apparently advised poorly. Here’s a nice win for the do-it-yourself folks buying the no-load shares. The advisor-sold version had far lower investor returns than did the DIY version. Whether because they showed up late or had a greater incentive to “churn” their clients’ portfolios, the advisor-led group managed to turn a great decade into an absolute zero (on average) for their clients.

“Eight Simple Steps to Starting Your Own Mutual Fund Family”

Sean Hanna, editor-in-chief at MFWire.com has decided to published a useful little guide “to help budding mutual fund entrepreneurs on their way” (“Eight Simple Steps,” April 21 2011). While many people spent one year and a million dollars, he reports, to start a fund, it can be a lot simpler and quicker. So here are MFWire’s quick and easy steps to getting started:

Step 1: Develop a Strategy

Step 2: Hire Expert Counsel

Step 3: Your Board of Directors

Step 4: The Transfer Agent

Step 5: Custodian

Step 6: Distribution

Step 7: Fund Accountant

Step 8: Getting Noticed

The folks here at the Observer applaud Mr. Hanna for his useful guide, but we’d suggest two additional steps need to be penciled-in. We’ll label them Step 0 and Step 9.

Step 0: Have your head examined. Really. There are nearly 500 funds out there with under $10 million in assets. Make sure you have a reason to be #501. Forty or so have well-above average five year records and have earned either four- or five-star Morningstar ratings. And they’re still not drawing investors.

Step 9: Plan on losing money. Even if your fund is splendid, you’re almost certain to lose money on it. Mr. Hanna’s essay begins by complaining about “the old boy network” that dominates the industry. Point well taken. If you’re not one of “the old boys,” you’re likely to toil in frustrated obscurity, slowly draining your reserves. Indeed, much of the reason for the Observer’s existence is that no one else is covering these orphan funds.

My suggestion: if you can line up three major investors who are willing to stay with you for the first few years, you’ll have a better chance of making it to Year Three, your Morningstar and Lipper ratings, and the prospect of making it through many advisors’ fund screening programs. If you don’t have a contingency for losing money for three to five years, think again.

Hey! Where’d my manager go?

Investors are often left in the dark when star managers leave their funds. Fund companies have an incentive to pretend that the manager never existed and certainly wasn’t the reason to anyone invested in the fund (regardless of what their marketing materials had been saying for years). In general, you’ll hear that a manager “left to pursue other opportunities” and often not even that much. Finding where your manager got to is even harder. Among the notable movers:

Chuck Akre left FBR Focus (FBRVX) and launched Akre Focus (AKREX). Mr. Akre made a smooth marketing move and ran an ad for his new fund on the Morningstar profile page for his old fund. Perhaps in consequence, he’s brought in $300 million to his new fund.

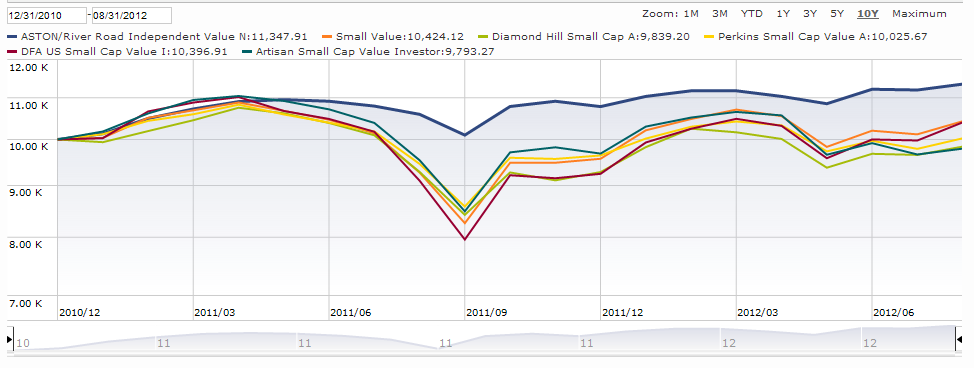

Eric Cinnamond left Intrepid Small Cap (ICMAX) to become lead manager of Aston/River Road Independent Value (ARIVX). Mr. Cinnamond’s splendid record, and Aston’s marketing, have drawn $60 million to ARIVX.

Andrew Foster left Matthews Asian Growth & Income (MACSX) after a superb stint in which he created one of the least volatile and most profitable Asia-focused portfolios. He has launched Seafarer Capital Partners, with plans (which I’ll watch closely) to launch a new international fund. In the interim, he’s posting thoughtful weekly essays on economics and investing.

If you’re a manager (or know the whereabouts of a vanished manager) and want, like the Who’s Down in Whoville to cry out “We are here! We are here! We are here!” then drop me a line and I’ll pass word of your new venue along.

The last Embarcadero story ever

It all started with Garrett Van Wagoner, whose Van Wagoner Emerging Growth Fund which returned 291% in 1999. Heck, all of Van Wagoner’s funds returned more than 200% that year before plunging into a 10-year abyss. The funds tried to hide their shame but reorganizing into the Embarcadero Funds in 2008, but to no avail.

In one of those “did you even blush when you wrote that?” passages, Van Wagoner Capital Management, investment adviser of the Embarcadero Funds, opines that “there are important benefits from investing through skilled money managers whose strategies, when combined, seek to provide enhanced risk-adjusted returns, lower volatility and lower sensitivity to traditional financial market indices.”

Uhh . . . that is, by the way, plagiarized. It’s the same text used by the Absolute Strategies Fund (ASFAX) in describing their investment discipline. Not sure who stole it from whom.

This is the same firm that literally abandoned two of their funds for nearly a decade – no manager, no management contract, no investments – while three others spent nearly six years “in liquidation”. Rallying, the firm reorganized those five funds into two (Market Neutral and Absolute Return). Sadly, they couldn’t then find anyone to manage the funds. On the downside, that meant they were saddled with high expenses and an all-cash portfolio during 2010. Happily, that was their best year in a decade. And, sadly, no one was there to enjoy the experience. Embarcadero’s final shareholder report notes:

While 2010 was difficult for the Funds, shareholders now have the benefit of new management utilizing an active investment program with expenses that are lower than previously applicable to the Funds. No shareholders remain in the Funds, and their existence will be terminated in the near future.

Uhh . . . if there are no shareholders, who is benefiting from new management? The “new management” in question is Graham Tanaka, whose Tanaka Growth Fund (TGFRX ) absorbed the remnants of the Embarcadero funds. TGFRX is burdened with high expenses (2.45%), high volatility (a 10-year beta of 140) and low returns (a whopping 0.96% annually over the decade). The sad thing is that’s infinitely better than they’re used to: Embarcadero Market Neutral lost 16.4% annually while Embarcadero Absolute Disast Return lost 23.8%.

Sigh: the Steadman funds (aka “Deadman funds” which refused, for decades, to admit they were dead), gone. American Heritage (a fund entirely dependent on penile implants), gone. Frontier Microcap (sometimes called “the worst mutual fund ever”), gone. And now, this. The world suddenly seems so empty.

Funds for fifty: the few, the proud, the affordable!

It’s increasingly difficult for small investors to get started in investing. Many no-load funds formerly offered low minimums (sometimes just $100) to entice new investors. That ended when they discovered that thousands of investors opened a $100 fund, adding a bit at first, then promptly forget about it. There’s no way that a $400 account does anybody any good: the fund company loses money by holding it (it would only generate $6 to cover expenses for the year) and investors end up with tiny puddles of money.

A far brighter idea was to waive the minimum initial investment requirement on the condition that an investor commit to an automatic monthly investment until the fund reached the normal minimum. That system helps enormously, since investors are likely to leave automatic plans in place long enough to get some good from them.

For those looking to start investing, or start their children in investing, look at one of the handful of no-load fund firms that still waives the minimum investment for disciplined investors:

- Amana – run in accordance with Islamic investment principles (in practice, socially responsible and debt-avoidant), the three Amana funds ask only $250 to start and waive even that for automatic investors.

- Artisan – one of the most distinguished boutique firms, whose five autonomous teams manage 11 domestic and international equity funds

- Aston – which specializes in strong, innovative sub-advised funds.

- Manning & Napier – the quiet company, M&N has a remarkable collection of excellent funds that almost no one has heard of.

- Parnassus – runs a handful of solid-to-great socially responsible funds, including the Small Cap fund which I’ve profiled.

- Pax World – a mixed bag in terms of performance, but surely the most diverse collection of socially-responsible funds (Global Women’s Equity, anyone) around.

- T. Rowe Price – the real T. Rowe Price is said to be the father of growth investing, but he gave rise to a family of sensible, well-run, risk-conscious funds, almost all of which are worth your attention.

Another race to the bottom

Two more financial supermarkets, Firstrade and Scottrade, have joined the ranks of firms offering commission free ETFs. They join Schwab, which started the movement by making 13 of its Schwab-branded ETFs commission-free, TD Ameritrade (with 100 free ETFs, Vanguard (64) and Fidelity (31). The commissions, typically $8 per trade, were a major impediment for folks committed to small, regular purchases.

That said, none of the firms above did it to be nice. They did it to get money, specifically your money. It’s their business, after all. In some cases, the “free” ETFs have higher expenses ratios than their commission-bearing cousins. In some cases, additional fees apply. AmeriTrade, for example, charges $20 if you sell within a month of buying. And in some cases, the collection of free ETFs is unbalanced, so you’re decision to buy a few ETFs for free locks you into buying others that do bear fees.

In any case, here’s the new line-up.

Firstrade (no broad international ETF)

Vanguard Long-Term Bond (BLV)

Vanguard Intermediate Bond (BIV)

Vanguard Short-Term Bond (BSV)

Vanguard Small Cap Growth (VBK)

iShares S&P MidCap 400 (IJH)

Vanguard Emerging Markets (VWO)

Vanguard Dividend Appreciation (VIG)

iShares S&P 500 (IVV)

PowerShares DB Commodity Index (DBC)

iShares FTSE/Xinhua China 25 (FXI)

Scottrade (no international and no bonds)

Morningstar US Market Index ETF (FMU)

Morningstar Large Cap Index ETF (FLG)

Morningstar Mid Cap Index ETF (FMM)

Morningstar Small Cap Index ETF (FOS)

Morningstar Basic Materials Index ETF (FBM)

Morningstar Communication Services Index ETF (FCQ)

Morningstar Consumer Cyclical Index ETF (FCL)

Morningstar Consumer Defensive Index ETF (FCD)

Morningstar Energy Index ETF (FEG)

Morningstar Financial Services Index ETF (FFL)

Morningstar Health Care Index ETF (FHC)

Morningstar Industrials Index ETF (FIL)

Morningstar Real Estate Index ETF (FRL)

Morningstar Technology Index ETF (FTQ)

Morningstar Utilities Index ETF (FUI)

Four funds worth your attention

Really worth it. Every month the Observer profiles two to four funds that we think you really need to know more about. They fall into two categories:

Most intriguing new funds: good ideas, great managers. These are funds that do not yet have a long track record, but which have other virtues which warrant your attention. They might come from a great boutique or be offered by a top-tier manager who has struck out on his own. The “most intriguing new funds” aren’t all worthy of your “gotta buy” list, but all of them are going to be fundamentally intriguing possibilities that warrant some thought. This month’s two new funds are:

Amana Developing World (AMDWX) is the latest offering from the most consistently excellent fund company around (Saturna Capital, if you didn’t already know). Investing on Muslim principles with a pedigree anyone would love, AMDWX offers an intriguing, lower-risk option for investors interested in emerging markets exposure without the excitement.

Osterweis Strategic Investment (OSTVX) is a flexible allocation fund that draws on the skills and experience of a very successful management team. Building on the success of Osterweis (OSTFX) and Osterweis Strategic Income (OSTIX), this intriguing new fund offers the prospect of moving smoothly between stocks and bonds and sensibly within them.

Stars in the shadows: Small funds of exceptional merit. There are thousands of tiny funds (2200 funds under $100 million in assets and many only one-tenth that size) that operate under the radar. Some intentionally avoid notice because they’re offered by institutional managers as a favor to their customers (Prospector Capital Appreciation and all the FMC funds are examples). Many simply can’t get their story told: they’re headquartered outside of the financial centers, they’re offered as part of a boutique or as a single stand-alone fund, they don’t have marketing budgets or they’re simply not flashy enough to draw journalists’ attention. There are, by Morningstar’s count, 75 five-star funds with under $100 million in assets; Morningstar’s analysts cover only eight of them.

The stars are all time-tested funds, many of which have everything except shareholders. This month’s two stars are:

Artisan Global Value (ARTGX): Artisan is the first fund to move from “intriguing new fund” to “star in the shadows.” This outstanding little fund, run the same team that runs the closed, five-star Artisan International Value (ARTKX) fund has been producing better returns with far less risk than its peers, just as ARTKX has been doing for years. So why no takers?

LKCM Balanced (LKBAX): this staid balanced fund has the distinction of offering the best risk/return profile of any balanced fund in existence, and it’s been doing it for over a decade. A real “star in the shadows.” Thanks for Ira Artman for chiming in with a recommendation on the fund, and links to cool resources on it!

Briefly Noted:

Morningstar just announced a separation agreement with their former chief operating officer, Tao Huang. Mr. Huang received $3.15 million in severance and a consulting contract with the company. (I wonder if Morningstar founder Joe Mansueto, who had to sign the agreement, ever thinks back to the days when he was a tiny, one-man operation just trying to break even?) It’s not clear why Mr. Huang left, though it is clear that no one suggests anyone did anything wrong (no one “violated any law, interfered with any right, breached any obligation or otherwise engaged in any improper or illegal conduct”), he’s promised not to “disparage” Morningstar.

On April 26, Wasatch Emerging India Fund (WAINX) launched. The fund focuses on Indian small cap companies and has two experienced managers, Ajay Krishnan and Roger Edgley. Mr. Krishnan is a native of India and co-manages Wasatch Ultra Growth. Mr. Edgley, a native of England for what that matters, manages Wasatch Emerging Markets Small Cap, International Opportunities and International Growth. Wasatch argues that the Indian economy is roaring ahead and that small caps are undervalued. Since they cover several hundred Indian firms for their other funds, they’re feeling pretty confident about being the first Indian small cap fund.

I somehow missed the launch of Leuthold Global Industries, back in June 2010.

The Baron funds have decided to ease up on frequent traders. “Frequent trading” used to be “six months or less.” As of April 20, 2011, it’s 90 days or less.

You might call it DWS not-too-International (SUIAX). A supplement to the prospectus, dated 4/11/11, pledges the fund to invest at least 65% of its assets internationally, the same threshold DWS uses for their Global Thematic fund. Management is equally bold in promising to think about whether they’ll buy good investments: “Portfolio management may buy a security when its research resources indicate the potential for future upside price appreciation or their investment process identifies an attractive investment opportunity.” DWS hired their fourth lead manager (Nikolaus Poehlmann) in five years in October 2009, fired him and his team in April 2011, and brought on a fifth set of managers. That might explain why they trail 96% of their peers over the past 1-, 3-, and 5-year periods but it doesn’t really help in explaining how they’ve managed to accumulate $1 billion in assets.

Henderson has changed the name of two of its funds: Henderson Global Opportunities is now Henderson Global Leaders Fund (HFPIX) and Henderson Japan-Asia Focus Fund is now Henderson Japan Focus (HFJIX). Both funds are small and expensive. Japan posts a relatively fine annualized loss of 6% over the past five years while Global Leaders has clocked in with a purely mediocre 1.3% annual loss over its first three years of existence.

ING plans to sell their Clarion fund to CB Richard Ellis Group by July 1, 2011. ING Clarion Real Estate (IVRIX) will keep the same strategy and management team, though presumably a new moniker.

Loomis Sayles Global Markets changed its name to Loomis Sayles Global Equity and Income (LGMAX).

The portfolio-management team responsible for Aston/Optimum Mid Cap (ABMIX) left Optimum Investment Advisers and joined Fairpointe Capital. Aston canned Optimum, hired Fairpointe and has renamed the fund Aston/Fairpointe Mid Cap. There will be no changes to the management team or strategy.

Thanks!

Mutual Fund Observer has had a good first month of operation. That wouldn’t have been possible without the support, financial, technical and otherwise, of a lot of kind people. And so thanks:

- To Roy Weitz and FundAlarm, who led the way, provided a home, guided my writing and made this all possible.

- To the nine friends who have, between them, contributed $500 through our PayPal to help support us.

- To the many people who used the Observer’s link to Amazon, from which we received nearly a hundred dollars more. If you’re interested in helping out, click on the “support us” link to learn more.

- To the 300 or so folks who’ve joined the discussion board so far. I’m especially grateful for the 400-odd notices that let us identify problems and tweak settings to make the board a bit friendlier.

- To the 27,000 visitors who’ve come by in the first month since our unofficial opening.

- To two remarkably talented and dedicated IT professionals: Brad Isbell, Augustana College’s senior web programmer and proprietor of the web consulting firm musatcha.com and to Cheryl Welsch, better known here as Chip, SUNY-Sullivan’s Director of Information Technology. They’ve both worked long and hard under the hood of the site, and in conjunction with the folks here, to make it all work.

I am deeply indebted to you all, and I’m looking forward to the challenge of maintaining a site worthy of your attention.

But not right now! On May 3rd I leave for a long-planned research trip to Oxford University. There I’ll work on the private papers of long-dead diplomats, trying to unravel the story behind a famous piece of World War One atrocity propaganda. It was the work of a committee headed by one of the era’s most distinguished diplomats, and it was almost certainly falsified. So I’ll spend a week at the school on which they modeled Hogwarts, trying to learn what Lord Bryce knew and when he knew it. Then off to enjoy London and the English countryside with family.

You’ll be in good hands while I’m gone. Roy Weitz, feared gunslinger and beloved curmudgeon, will oversee the discussion board while I’m gone. Chip and Brad, dressed much like wizards themselves, will monitor developments, mutter darkly and make it all work.

Until June 1 then!

David